George Soros discusses his principles of fallibility and reflexivity, and their implications for financial markets, social systems, and economic theory.

Skip ahead

- Falsifiability and truth

- Principle of Fallibility

- Principle of Reflexivity

- Financial playgrounds

- Bubbles and super bubbles

- Fat tails and uncertainty

- New frontiers

Falsifiability and truth

Philosopher Karl Popper says that we cannot know anything with ultimate certitude. While confirmatory evidence may add credibility to a theory or hypothesis, it cannot prove it true, as it takes only one new observation to contradict everything we know. And even if we are not yet in possession of such information, we cannot say that no such evidence will ever come along. For this reason, we ought to be skeptical of ideologies that promise absolute truth.

Investor George Soros was a student of Karl Popper during his time at the London School of Economics. And the contradiction between Popper’s principle of falsifiability and the assumption of perfect knowledge in orthodox economics gave him pause. The latter in particular was not consistent with his experience in financial markets. Indeed, it led him to develop his own principles of fallibility and reflexivity, which Soros argues is more representative of real world behavior.

Principle of Fallibility

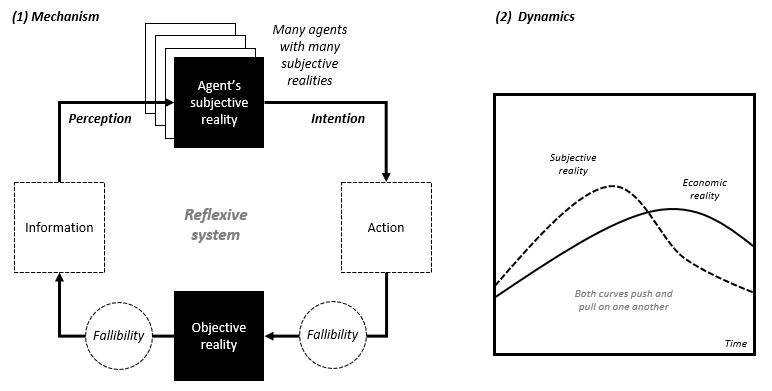

The first of Soros’ contributions is the Principle of Fallibility. Soros argues that an observer’s perception of their reality is always partial, subjective, and distorted. Sure, they can gather information and develop models to understand their environment. But it is always, in one way or another, “biased or inconsistent or both”.

This is because our world is immensely complex; and we ourselves are functions of evolutionary and cultural history. Books like Thinking, Fast and Slow, The Knowledge Illusion, and Factfulness, for instance, talk at length about the biases and instincts that guide our perception; and how we rely on narratives and heuristics to simplify and comprehend our world.

Principle of Reflexivity

The second of Soros’ contributions is the Principle of Reflexivity. It is a reminder that perceptions and beliefs affect reality through behavior. Soros notes, for example, that investors’ beliefs about market efficiency will influence their strategy, which influences market outcomes and their subsequent beliefs in turn. Other examples of reflexivity include parimutuel systems, self-fulfilling prophecies, and bandwagon effects.

Circularity, slippage, and unintended consequences

Reflexivity requires us to see the circularity in the systems we are talking about. That is, there is no truly independent variable. Soros likens reflexivity to the self-referencing loop in the Liar’s Paradox (“this sentence is false”). In most natural experiments, the act of thinking and observing does not affect the phenomena of interest.

Your feelings cannot change the laws of motion that move our planets around the sun. This is true no matter how angrily, or fearfully, you study them. But, as we know, this isn’t always the case with social phenomena. Your feelings and actions shape and are shaped by the feelings and actions of others.

What’s more, fallibility implies some degree of “slippage” or uncertainty, as people learn, perceive, and act imperfectly. That is, what we experience subjectively can differ materially from what actually is. Mix in some reflexivity, and you can generate a plethora of interesting social behaviors and unintended consequences.

Figure I. A reflexive system

Far-from-equilibrium and feedback loops

Unlike mainstream economists, Soros is less concerned with equilibrium conditions. Rather, he seeks to identify the positive (self-reinforcing) and negative (self-correcting) feedback loops that fallibility and reflexivity can produce. To Soros, competitive equilibrium in economic theory is “an extreme case of negative feedback” and self-correction. It is a “limiting case” because fallibility and reflexivity together can sustain far-from-equilibrium conditions for extended periods of time.

Financial playgrounds

Soros meant for his principles to be a general description of social and economic ‘thinking’ systems. But it lends itself immediately to application and testing in finance (in part because Soros is another billionaire investor who disagrees with the efficient market hypothesis).

Firstly, Soros argues that the price of financial assets are not always an accurate measure of fundamental value. Sometimes, “[prices] do not even aim to do so”. After all, prices are an aggregation of future expectations. And expectations, as we’ve said, are sometimes fallible.

Secondly, market participants, through the process of reflexivity, may either correct or reinforce these expectations. In this way, disequilibrium does not always occur randomly or exogenously as orthodox models might suggest. Narratives and animal spirits can swing subjective beliefs and expectations away from economic reality, sometimes for extended periods of time.

“If agents act on the basis of their imperfect understanding, equilibrium is far from a universally and timelessly prevailing condition of financial markets. Markets may just as easily tend away from a putative equilibrium as toward it. … Whereas economics views equilibrium as the normal, … I view such periods of stability as exceptional. Rather I focus on the reflexive feedback loops that characterize financial markets and cause them to be changing over time. … Markets may give the impression that they are always right, but the mechanism at work is very different from that implied by the prevailing paradigm”.

George Soros. (2013) Fallibility, Reflexivity, and the Human Uncertainty Principle. Journal of Economic Methodology.

Bubbles and super bubbles

Financial bubbles are among the best examples of fallibility and reflexivity at work. They emerge when perceived reality diverges significantly from the underlying economic reality. While the duration and magnitude of bubbles and correction are unpredictable, they tend to exhibit “an internal logic” with four phases: “[1] inception; [2] a period of acceleration, interrupted and reinforced by successful tests; [3] a twilight period; and [4] the reversal point or climax.”

It’s also important to recognize that multiple feedback loops can act at once. Amidst multiple manias, panics, and crises in the 1990s and 2000s, Soros notes, was the super-bubble of credit and leverage. He originally believed that the financial crises in emerging markets during the 1990s would trigger the super bubble’s “turning point”. Instead, it continued to grow, culminating in an even greater meltdown following the subprime crisis.

Currencies and institutions

Reflexivity manifests itself in many economic domains. Soros describes, for example, how “freely floating exchange rates tend to move in large, multi-year waves”. The underlying equilibrium is elusive (if it even exists at all). The interplay between investors and institutions is similarly reflexive. The dynamics of monetary policy, financial regulation, and risk migration, in response to market conditions, are good examples of this.

Fat tails and uncertainty

It is common for practitioners in financial economics and econometrics to assume a neat, normal distribution to the spread of movements in prices. As Benoit Mandelbrot found in the Variation of Certain Speculative Prices, and as others later showed, prices can and do exhibit “fat tails” from time to time.

Indeed, as Nassim Taleb explains in the Statistical Consequences of Fat Tails, many biases and incorrect conclusions in the social sciences are a product of incorrect assumptions about distributions. In finance, this can culminate in spectacular failures, like the miscalculations that led to the rise and downfall of Long Term Capital Management.

Soros reminds us that people use dichotomies, narratives, and other heuristics to cope with the immensity of information around them. Such tools can imply a ‘tipping point’ in which behavior switches from self-correction to self-reinforcement, and vice versa. Furthermore, standard theory does not account for “time pressure” under crises episodes. When people do not have the time to fact-find and rationalize, things “can spin out of control”.

Non-normal is normal

Fallibility and reflexivity suggests that the non-normal distributions we see from time to time are not all that surprising. It follows that the rules and models we use for normal conditions may not help us in extreme environments. Soros laments, for example, that while he anticipated the market’s response during the subprime crisis, he underestimated its volatility and took too large a position — “[he] learned the hard way that the range of uncertainty is also uncertain”.

“Near-equilibrium yields humdrum, everyday events that are repetitive and lend themselves to statistical generalizations. In contrast, far-from-equilibrium conditions give rise to unique, historic events in which outcomes are uncertain…. Rules that can usefully guide decisions in near-equilibrium conditions can be misleading in far-from-equilibrium situations.” .

George Soros. (2013) Fallibility, Reflexivity, and the Human Uncertainty Principle. Journal of Economic Methodology

New frontiers

Soros believes that Alan Greenspan misrepresented the dotcom bubble in the late 1990s with the quip: “irrational exuberance”. Bubbles are not completely irrational because rational, self-interested, profit-seeking speculators like Soros will “add fuel to the fire… when [they] see a bubble forming”.

Regulators need to do more, Soros believes, to subdue bubbles that the market cannot contain. Responding before the fact, of course, is not easy. Mistakes will be made. But reactive monetary policy and fiscal stimulus alone is not enough. Soros argues for greater credit controls that vary with the market’s animal spirits; better measures of national and global systemic risk; and solutions that target the moral hazard and dangers that come with being too big to fail.

“The efficient market hypothesis has certainly proved inadequate… The entire edifice of global financial markets that has been erected on the false premise that markets can be left to their own devices has to be rebuilt from the ground up”.

George Soros. (2009). The Soros Lecture at the Central European University.

Shackles and progress

Finally, economics and finance needs to free itself from the shackles of physics envy and assumptions that do not conform to reality. We have to remember that social systems are fallible and reflexive. Incorrect beliefs can and do distort our behavior and reality. The upshot, however, is more hopeful according to Soros. Reflexivity in the end provides an ambitious but noble goal for the social sciences: to develop theories and models that guide our behavior for the better.

As Soros writes:

“Economic theory should not be expected to produce universally valid laws that can be used reversibly to explain and predict historic events. I contend that the slavish imitation of natural science inevitably leads to the distortion of human and social phenomena. [And] why should social science confine itself to passively studying social phenomena when it can be used to actively change the state of affairs?”

George Soros. (2009). The Soros Lecture at the Central European University.

Sources and further reading

- Soros, George. (2009). General Theory of Reflexivity. The Soros Lectures at the Central European University. Open Society Foundations.

- Soros, George. (2009). Financial Markets. The Soros Lecture at the Central European University. Open Society Foundations.

- Taleb, Nassim. (2020). Statistical Consequences of Fat Tails: Real World Pre Asymptotics, Epistemology, and Applications.

- Bernanke, Ben., Paulson, Henry., and Geithner, Timothy. (2019). Firefighting: The Financial Crisis and Its Lessons.

- Mandelbrot, Benoit. (1963). The Variation of Certain Speculative Prices. Journal of Business, 36, 394– 419.

Recent posts

- Arguing with Zombies — Paul Krugman on Bad Models and False Idols

- Raghuram Rajan on Financial Development and the Making of a Riskier World

- The Winner’s Curse — Richard Thaler on the Anomalies of Auctions

- The Market for Lemons — George Akerlof on Asymmetry, Uncertainty and Information

- Reflexivity and Resonance — Beunza & Stark on Quantitative Models and Systemic Risk

- Power Laws — Mark Newman on Solar Flares, Gambling Ruins and Forest Fires

- Heresies of Finance — Benoit Mandelbrot on Volatile Volatility and Valueless Value

- Financial Instability Hypothesis — Hyman Minsky on Ponzi Finance and Speculative Regimes