The life of a price bubble

Price bubbles in financial markets often seem to take a life of their own. Robert Shiller parallels the phenomena to an infectious disease. Because our belief systems and collective narratives are deeply intertwined, emotions and behavior can spread contagiously. A surge of enthusiasm, for example, may encourage traders to bid asset prices up. Interpreting this as good news, other traders enter the fray, pushing prices even higher. This process repeats itself until the narrative is no longer believable and expectations reverse—popping the bubble in spectacular fashion.

Mountains and molehills

As Ben Graham would say, people make “mountains out of molehills and exaggerate ordinary vicissitudes.” Our animal spirits, you see, act as a confidence multiplier. Like a hall of mirrors, our sentiments and behaviors influence the sentiments and behaviors of others, and vice versa. Intellectual hubris, historical amnesia, rational speculators, and the fear-of-missing-out add only to these dynamics. And as we witnessed throughout the dotcom bubble, the stock prices of companies like Boo.com, Pets.com, Webvan, Freei, and 360networks can rise as extravagantly as they fall. What appears sensible to the individual can become insanity in the aggregate.

Overreaction and underreaction

Of course, the theoretical view that markets are always efficient and self-correcting is insufficient. The dotcom bubble, for example, took nearly seven years to dissipate. Overreaction and underreaction are recurring themes in the course of financial history. In his book Inefficient Markets, economist Andrei Shleifer attributes these twin tendencies to two behavioral traits: representativeness, in which recent events are assumed to be representative of the future; and conservatism, in which investors are slow to update their views as new evidence comes along. Representativeness and conservatism together, he says, can explain the momentum and inertia we observe in market prices.

The anatomy of a price bubble

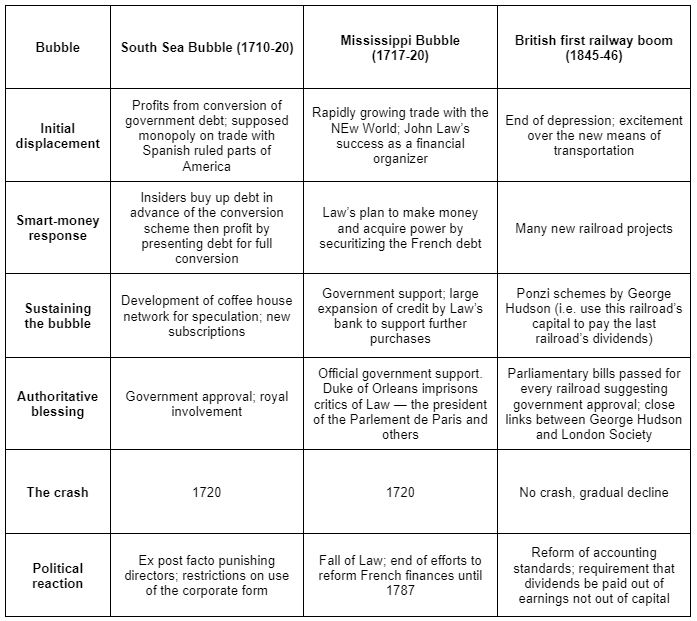

Drawing on Charles Kindleberger’s Manias, Panics, and Crashes, Shleifer adds that price bubbles tend to go through six phases:

- Initial displacement

- Smart-money response

- Sustaining the bubble

- Authoritative blessing

- The crash

- Political reaction

Displacement, for starters, typically begins with good news and windfall profits for early investors. Noticing this, noise traders and smart-money will increase the supply of assets and pump the bubble in anticipation of future returns. This creates a positive feedback loop.

Moreover, the bubble persists not only on its own momentum, but on the visceral narratives and “authoritative blessings”. Disconfirming evidence is shunned by the masses, while some experts, celebrities, and public figures provide greater legitimacy to the entire façade. As a result, more and more people participate in fear-of-missing-out. And other causes of human misjudgment, like the bad incentives and social proof, add further to the feedback loop.

But if the bubble is based on false economics, it must eventually end, much like a Ponzi scheme that runs out of buyers. The crash is usually fast and violent as traders race for the exits in fear of being the last person standing. Collapse is then followed by public outrage and political reactions, especially if the episode is severe and protracted.

As Ben Graham surmises:

“When the going is good and new issues are readily salable, stock offerings of no quality at all make their appearance. They quickly find buyers; their prices are often bid up enthusiastically… Wall Street takes this madness in its stride, with no overt efforts by anyone to call a halt before the inevitable collapse in prices. … When many of these minuscule but grossly inflated enterprises disappear from view, … it is all taken philosophically enough as “part of the game.” Everybody swears off such inexcusable extravagances — until next time.”

Benjamin Graham. (1973). The Intelligent Investor.

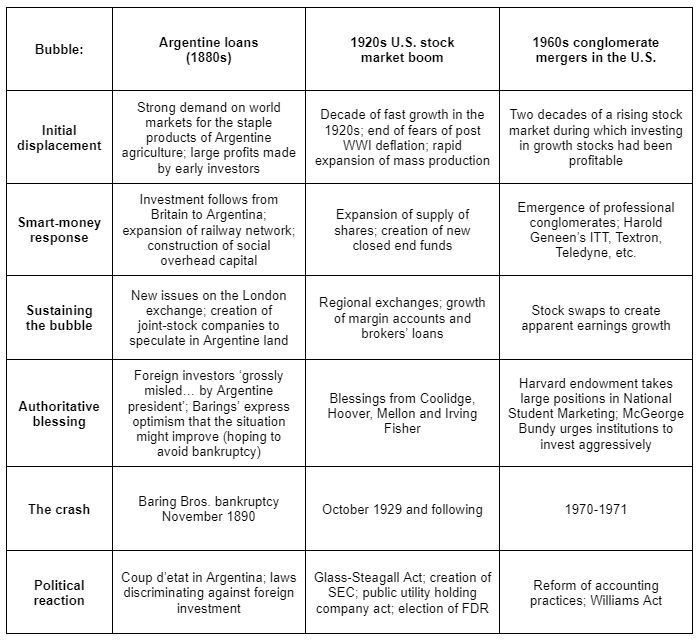

Indeed, many bubbles across financial history appear to conform to this pattern. Shleifer catalogued many of them to illustrate the point. I’ve included selected excerpts in Table 1 and Table 2 for your perusal.

Table 1: The anatomy of a price bubble

Table 2: The anatomy of a price bubble (continued)

Safe houses and cocaine brains

Moreover, in his book Adaptive Markets, Andrew Lo writes that “winning money… had the same effect on the brain as a cocaine addict getting a fix.” Something in the social frenzy, paper gains, and “false sense of security” make investors euphoric. In a financial bubble, “prices are high because investors expect them to go higher”, Shleifer adds. Investors grow tolerant or oblivious to risk. Indeed, ‘safe-as-houses’ was quite the mantra in the runup to the subprime meltdown. People couldn’t imagine anything else. But the extraordinary “growth rates implied by extreme market valuations have never materialized in U.S. history”, Shleifer writes. “It is the stock prices that adjust down rather than earnings that adjust up.”

Firefighting

If markets are not always efficient or self-correcting, then there remains an important role for governments and institutions to play. For one, investor protection is important, Shleifer notes. Don’t get this twisted, however. We aren’t talking about compensation for fools and charlatans that make dumb bets and risky decisions. We are talking about protection against theft, expropriation, conflicts of interest, transfer pricing, and excessive compensation. Financial markets “disintegrate”, Shleifer writes, when we cannot protect investors from wrongdoing.

More controversial is the government’s role as a lender of last resort. Indeed, intervention during the subprime meltdown staved off economic implosion. But as Ben Bernanke and colleagues explain in Firefighting, bailouts have also added to public distrust, political polarization, and the moral hazard in finance. It’d be better, of course, if we could avoid crises altogether. But how far should authorities go to quell emerging bubbles and discourage speculation? Can they even? If bubbles were so easy to spot and deflate before-the-fact, we would not have them in the first place. Of course, direct intervention isn’t the only prescription. Adequate capital, liquidity, credit, and quality controls can help to reduce the frequency and severity of unseen danger—assuming our institutions possess enough self-control during the good times to keep the rules in check.

Clearly, we do not have enough room or time to get into the details here. But I’ll end by saying the obvious. Financial markets are complex systems. To understand and ameliorate price bubbles is no small order. It took medicine many millennia to learn and treat the human body. Finance and economics, by contrast, as a discipline, is still in its infancy. There remains a lot for us to learn about the nature of society and market economy.

Sources and further reading

- Shleifer, Andrei. (2000). Inefficient Markets: An Introduction to Behavioral Finance.

- Lo, Andrew. (2017). Adaptive Markets: Evolution at the Speed of Thought.

- Bernanke, Ben., Paulson, Henry., & Geithner, Timothy. (2019). Firefighting: The Financial Crisis and Its Lessons.

- Akerlof, George., & Shiller, Robert. (2009). Animal Spirits: How Human Psychology Drives the Economy, and Why It Matters for Global Capitalism.

- Graham, Benjamin. (1973). The Intelligent Investor: The Definitive Book on Value Investing. 4th Revised Edition.

Latest posts

- Arguing with Zombies — Paul Krugman on Bad Models and False Idols

- Raghuram Rajan on Financial Development and the Making of a Riskier World

- The Winner’s Curse — Richard Thaler on the Anomalies of Auctions

- The Market for Lemons — George Akerlof on Asymmetry, Uncertainty and Information

- Reflexivity and Resonance — Beunza & Stark on Quantitative Models and Systemic Risk

- Power Laws — Mark Newman on Solar Flares, Gambling Ruins and Forest Fires

- Heresies of Finance — Benoit Mandelbrot on Volatile Volatility and Valueless Value

- Financial Instability Hypothesis — Hyman Minsky on Ponzi Finance and Speculative Regimes

- Constructing a Market — MacKenzie and Millo on Performativity and Legitimacy in Economics

- The Wrong Track — Benoit Mandelbrot on the Future of Finance