Game theory isn’t just about solving the game. It’s also about transforming the game, too. Sometimes, players must change the payoffs, options, and move orders to achieve a better outcome. Commitments, threats, and promises, are tools for such purposes. They may deter others from certain actions or compel them to take desired actions. In this post, we explore the intuition behind these game theoretic concepts.

Commitments, threats and promises

Commitments are unconditional moves that a player makes upfront. A commitment locks them into a set of payoffs and choices that others must now incorporate into their decision-making. Threats and promises, by contrast, are conditional response rules. Threats usually turn into punishments when the threatened player misbehaves, while promises generates rewards when the promised player fulfills some condition. Players sometimes mix-and-match commitments, threats, and promises to incentivise desired outcomes.

The game of life

Do you have difficulties sticking to your New Year’s resolutions? Many people break their diet plans and exercise goals because the competing temptations are just too strong. Sometimes, we must restructure the consequences to achieve desired results. ABC Network tested this idea in their reality television program Life: The Game.^ To incentivize their weight loss on their show, the studio threatened overweight participants with shame. They would publish photographs of participants in swimwear on national television if the participants failed to reach their target weight. Unlike a weak New Year’s resolution, the participant’s irrevocable participation on the show, coupled with the threat of shame, incentivized most of them to lose weight.

^ Case study sourced from Avinash Dixit and Barry Nalebuff’s The Art of Strategy (1993).

Deterrence and compellence

Sometimes, we want to restructure the game to deter or compel someone else. Deterrence seeks to dissuade someone from pursuing an action they otherwise would. Deterrence, according to game theorist Thomas Schelling, involves “rigging the trip-wire” first. This puts the onus on the provocateur to choose wisely (or to otherwise risk punishment). Compellence, by contrast, seeks to persuade someone to do something they otherwise would not. It involves taking actions that ceases only after the target has complied. Threats, promises, and commitments are tools for deterrence and compellence.

“To deter, one digs in, or lays a minefield, and waits — in the interest of inaction. To compel, one gets up enough momentum (figuratively, but sometimes literally) to make the other act to avoid collision.” Thomas Schelling. (1966). Arms and Influence.

Personally, I find it most helpful not to get too bogged down in definitions and semantics. It’s better to understand the possibilities than to get lost in jargon. Let’s continue instead with an example.

Empires and alliances (WIP)

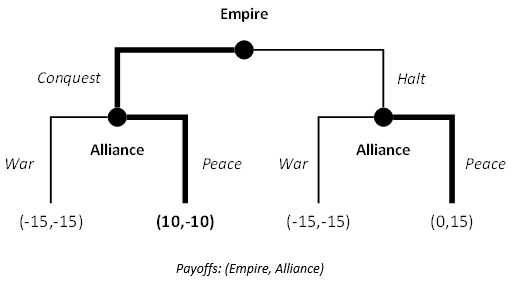

Let’s consider a territorial challenge between the Empire and the Alliance. In this game, the Empire is choosing between further conquest or halting its expansion. Following this move, the Alliance must choose a response – to retaliate with war or tolerate with peace. We summarise the players, moves and payoffs in a decision tree as follows:

Empire v Alliance I

What is the solution to this game?

Subgame perfect Nash equilibrium (SPNE)

The Alliance, of course, does not want the Empire to expand. And the Empire knows this. But the Empire also knows that the Alliance doesn’t want war. The payoffs suggest that the Alliance has a strictly dominant strategy to choose peace. Indeed, the SPNE strategic profile of this game sees: the Empire pursue conquest; and the Alliance tolerate peace, whether the Empire expands or not. Under the SPNE, the Alliance gets a payoff of -10, while the Empire enjoys a payoff of +10.

Incredible threat

Indeed, the SPNE is an undesirable outcome for the Alliance. It would rather the Empire halt its expansion, and for both nations to maintain peace. While the Alliance could threaten the Empire with war, the threat fails because the Empire knows that if they did expand, it remains in the Alliance’s best interest to uphold peace. Economists like to call this an incredible threat. Not because the threat is extraordinary, but because it is not credible to the threatened player.

Schelling on parenting: “In personal life I have sometimes relied, like King Lear, on the vague threat that my wrath will be aroused… if good behavior is not forthcoming, making a tentative impression on one child, only to have the threat utterly nullified by another’s pointing out that “Daddy’s mad already.”” Thomas Schelling. (1966). Arms and Influence.

Commit to deter

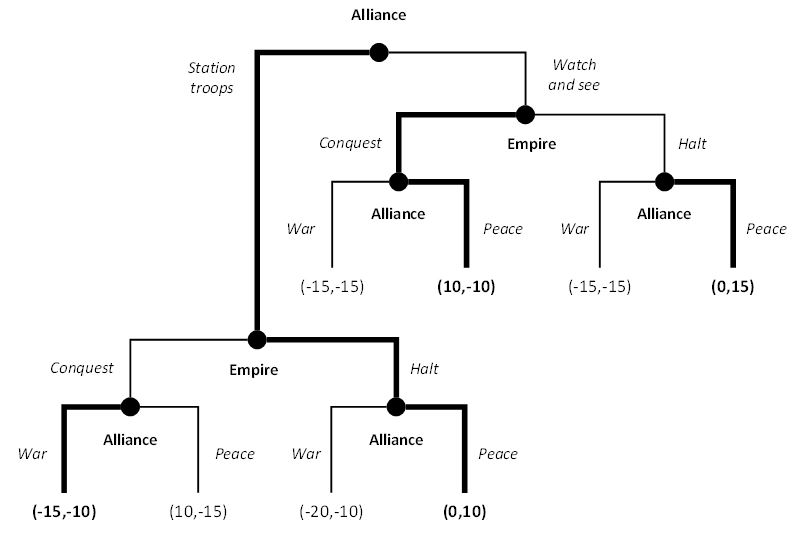

Suppose the Alliance didn’t have to wait and see whether the Empire expanded or not. Let’s say they have an option to station troops upfront in neutral territory. Its effect is twofold. Firstly, stationing troops improves military readiness, reducing the net cost of engagement to the Alliance, should war take place. Secondly, it reduces the net payoff to the Alliance during peace time, as stationing troops in neutral territory is resource intensive and politically unfavourable. If the Alliance chooses to watch-and-see instead, then the game reverts to the original structure and payoffs we saw above. We summarise the players, moves and payoffs in this expanded game as follows:

Empire v Alliance II

Subgame perfect Nash equilibrium (SPNE)

What is the SPNE strategic profile of this game? Through backward induction, the Alliance will station troops in neutral territory. Following this, the Alliance will choose war should the Empire choose conquest, and peace should the Empire halt. And if, for whatever reason, the Alliance finds itself in the watch-and-see subgame, then it will choose peace, regardless of what the Empire decides. Conversely, under the SPNE, the Empire will halt its expansion should the Alliance station troops and pursue conquest should the Alliance wait-and-see. The path that materialises under the SPNE, of course, has the Alliance stationing troops, the Empire halting expansion, and the Alliance upholding peace. The payoff associated with this solution is zero to the Empire, and 10 to the Alliance – a far more favourable outcome to the Alliance than the SPNE of the previous game.

Credible threat

In this way, the Alliance’s commitment to station troops in neutral territory is a credible threat. For the Alliance, the commitment makes war relatively more attractive. The Empire can see the change in payoffs and anticipates war should they proceed with conquest. By “rigging the trip-wire” with the stationing of troops, the Alliance’s commitment provides an effective deterrent.

Credibility and information

Strategy involves the reshaping of relative payoffs to guide interactions to your favour. To deter and compel effectively, information and clarity play important roles. After all, how can we expect adversaries to change their behaviour if they do not know the rules, conditions, and boundaries of the threats and promises that affect them? Many social and cultural institutions, from sports to religion, adopt simple rules, rewards, and punishments for this very reason.

What’s more, the target must know or believe that the threatener or promiser will follow through. Without credibility, players will not the commitment, threat, or promise seriously. How then might we foster credibility as to enhance the effectiveness of our threats, promises, and commitments? Avinash Dixit and Barry Nalebuff offer several suggestions in The Art of Strategy:

Reputation

Reputation communicates a history (and expectation) of behaviour to players. The mafia, for example, has a reputation for breaking legs. Small time criminals might think twice before upsetting them. Likewise, you might try a new but untested product because the company’s brand is associated with quality. Reputations are sometimes self-reinforcing. Politicians that are deeply committed to a particular reputation will act and invest in ways to preserve that image – no matter how costly. Right or wrong or sensible, it is probably credible.

Incremental steps

If a high level of commitment is necessary, players can seek smaller levels of commitment first and build incrementally. Take large construction projects for example. Buyers typically pay an initial deposit to get builders to commence the job. But buyers send the final payment through only after the job is completed to satisfaction. Staged payments give both parties the confidence to participate in what might otherwise be a risky venture to both sides.

Burning bridges

Another option is to eliminate options and exit strategies. “Cutting off communication” and “burning bridges behind you”, Dixit and Nalebuff say, are popular commitment devices because they leave the player with no alternatives. In a previous post, we showed that players can win the Game of Chicken by committing credibly to staying the course (not swerving). The rational second mover must swerve away (become chicken) or otherwise meet demise. Commitments are especially credible when they are truly irreversible.

“Skillful diplomacy, in the absence of uncertainty, consists in arranging things so that it is one’s opponent who is embarrassed by having the “last clear chance” to avert disaster by turning aside or abstaining from what he wanted to do.” Thomas Schelling. (1966). Arms and Influence.

Contracts and institutions

Contracts and legal institutions can help to deter and compel. An employer, for example, can threaten to fire an employee if the employee does not perform her duties adequately. Likewise, the employee can appeal to authorities if the employer breaches their agreement. Informal familial, cultural, and religious institutions are influential forces as well. The threat of excommunication from high school cliques, religious communities, and military units, for example, can influence behaviour greatly.

Cost, timing, and magnitude

Is it better to threaten or promise? One important consideration is cost. Threats are usually most costly when it fails. Not only do you fail to achieve your preferred outcome, but you also have to punish your opponent to maintain credibility. But threats are quite cost effective when it succeeds. Your adversary does what you like without necessitating further action. Promises, by contrast, are more costly when it succeeds. While you’ve achieved your preferred outcome, you have to reward your peer to maintain credibility. If your promise fails, you don’t have to payout, which is nice. But you remain stuck in an unideal situation.

Time to deter and compel

Of course, actual costs are context sensitive. Timing is also an important issue. Deterrence, for example, tends to be more indefinite in nature. Compellence, by contrast, involve specific timeframes. Threats and promises may have more natural partners for this reason. In many cases, players may pursue a mix of threats and promises to induce desired behaviours – like parents and children.

A question of size

Threats are more likely to succeed when it’s large. Life imprisonment discourages murder. A scolding from the judge might not. This doesn’t mean, however, that players should impose colossal threats on one another to ensure successful deterrence.

Remember, threats and promises must be credible. Threatening nuclear warfare in response to any territorial dispute, big or small, seems unbelievable. And if the threat fails, you have to punish to maintain credibility. The strongest punishment might be too painful to you and your opponent. Economic sanctions, by contrast, might encourage your adversaries to think twice. What’s more, it is often unclear what scale is necessary for a threat to succeed. It is not a game of pure calculation. Psychology and emotion can matter.

Sometimes, it is better to begin with smaller punishments or rewards, and scale in gradual increments until the desired behavior is achieved. We have more to say on this when we talk about the game of brinkmanship.