Predictably irrational

We like to believe that we possess agency—that we are rational, in control, and able to make good decisions. The reality is, however, “that we are not only irrational, but predictably irrational”, writes economist Dan Ariely. Our behaviors “are neither random nor senseless.” We tend to do the same things in the same way. But if we can understand how and why this is so, then we may learn something about ourselves. And if we’re lucky, we might find new ways to think and decide more effectively.

Relativity in economics

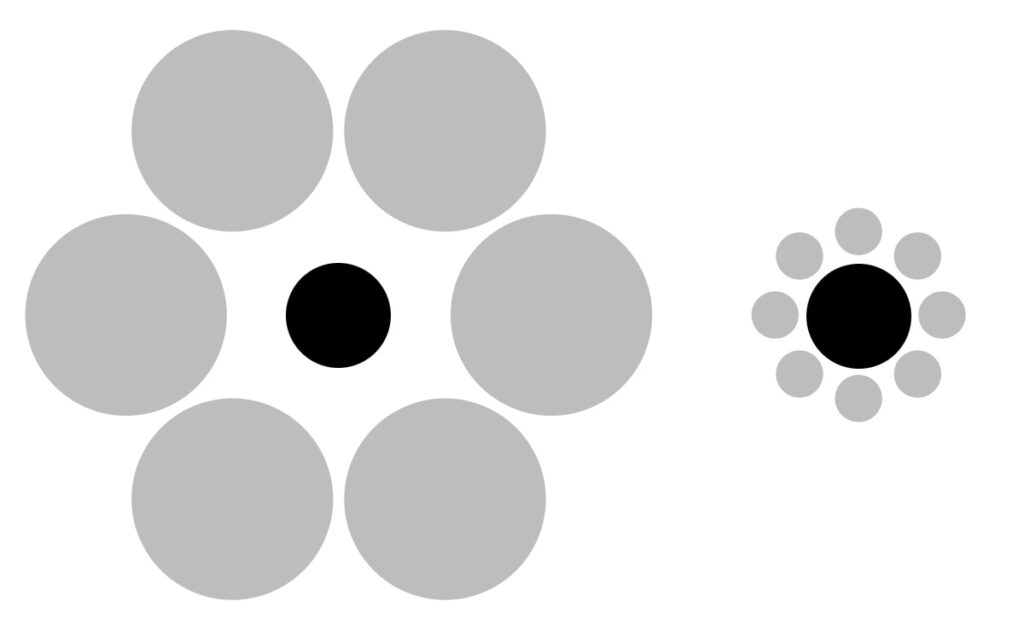

In contrast to standard economic theory, people rarely make decisions on absolute terms. “Most people don’t know what they want unless they see it in context”, Ariely reminds. “Everything is relative.” Take, for example, the Ebbinghaus illusion below (Figure 1). Our rational brain tells us that the two black circles are identical in size. But our intuitive brain cannot help but see them differently when they are surrounded by smaller and larger grey circles. Now imagine how difficult it must be to perceive real life problems correctly when the values and alternatives we face are more complex and ambiguous. To draw correct conclusions, we have to override our first impressions with careful analysis.

Figure 1: Ebbinghaus illusion

Decoy prices

If we’re not careful, businesses will exploit our bias for relative thinking. Ariely noticed, for example, that The Economist magazine once offered readers one of three annual subscription packages: (1) Internet-only for $59; (2) Print-only for $125; and (3) Print-and-Internet for $125. Which subscription do you prefer? Which one offers the best value?

When Ariely ran these options by MIT’s Sloan School of Management, 16% of students went for the first package, zero for the second, and 84% for the third. That’s good news, right? MIT’s graduates realized that the second option was inferior to the third. Being the rational graduates that they are, they selected accordingly.

However, when Ariely ran the same price-lists, but without the second inferior option on display, purchasing habits changed. Under this new menu, 68% of students bought the internet-only package, while 32% opted for the print-and-internet bundle. By removing the inferior decoy, more students purchased the cheaper subscription. Relative thinking was rearing its head.

Similarly, Ariely describes the time when Williams-Sonoma launched their bread bakery machine at a $275 price tag. Sales, however, did not take off. Bread machines were rather novel for its time and people were uncertain of its value to them. In response, a marketing consultancy advised Williams-Sonoma to introduce a second, larger bread maker model at a 50 percent price premium. The strategy worked. But sales climbed not because the new machine was of superior make or value to customers. Rather, “consumers now had two models of bread makers to choose from”, Ariely explains. Like a subscription with The Economist, Williams-Sonoma used relative prices to make customers feel as though the original model was within their price range and budget.

Habitual comparers

Indeed, we are habitual comparers. We compare everything, from jobs and salaries to homes and cars. What’s more, our sampling choices are usually born out of convenience. Parents compare their children to their cousins and classmates. Workers compare their salaries to their friends and colleagues. Teenagers compare themselves to friends and influencers on social media.

While these habits are sometimes helpful, it is also a common cause of misery and bitterness. Jealousy and envy feeds on and into our comparisons. Studies show, for example, that “the happiest people are not among those with the highest personal income”, Ariely writes. Yet many of us continue on the hamster wheel in chase of the next promotion. This obsession is due in part to self-image preservation. We care about social standings and how we are perceived by our peers. As a result, the “rich now envy the super rich.”

Diamonds and arbitrary coherence

Moreover, when it comes to comparisons, there’s a sort of “arbitrary coherence” to it. For instance, why are diamonds so expensive when there “are mines full of more diamonds than humanity could ever want or need?” Whether right or wrong or arbitrary, perceived scarcity and emotional marketing can generate demand. The high price in turn helps the sellers to reinforce common beliefs. First impressions are important too. “Once those prices are established in our minds, they will shape not only present prices but also future prices”, Ariely explains. A five cent increase in the price of milk, for example, will make headlines. But would people have stirred just as much had prices been at this new level in the first place?

From the price of milk to diamonds, pre-existing ‘anchors’ affect the way people react. Ariely points, for example, to the strategy that Starbucks founder Howard Shultz used to to sell high margin beverages across the United States. For starters, Starbucks looked to distinguish itself from Dunkin’ Donuts and other players in terms of ambience, experience, and quality. Frappuccino, macchiato, americano, and other exotic sounding items began to enter the American coffee vernacular. Most interesting, I thought, was Starbucks’ decision to rename their cup sizes. Small became short, medium became tall, large became grande, and very large became venti. Much of the Starbucks strategy, you see, was about eroding the anchors that Americans held about takeaway coffee. And it worked.

All of this is a reminder that demand and supply are not static, independent curves as is typically assumed in economic textbooks. Consumers do not always know what they want. Nor can they compare everything in their budget constraint with rational completeness. Many supply-side factors, from research & development to marketing & sales, play a role. The diversity we see in the marketplace is a product of this never-ending entanglement between demand and supply.

Beer, vinegar, and expectations

Related to comparisons and anchors is the role of expectations. Ariely wondered, in particular, whether differences in expectations can change our psychology and physiology. So like any good behavioral economist, he ran experiments with plenty of alcohol.

In one experiment, Ariely got college students to sample a new alcoholic concoction of vinegar-in-beer. Their feedback were surprising. “Students who found out about the vinegar after drinking the beer liked the beer much better than those who were told about the vinegar up front.” They actually liked the beer as much as those who were not told about the vinegar at all. Strange, no? While we think we know what we like, we are not in full control of the contexts that shape our fuzzy beliefs and expectations. Placebos and natural remedies persist in part for this reason.

Similarly, in another experiment, Ariely offered bar goers a range of beers to sample. What’s interesting is that overall group preferences were dependent on whether people made their orders in private or by ordering out loud and in sequence. The study found that when people make their orders publicly, “they order more types of beer per table.” This suggests that people either want variety or they want to convey their individuality by deviating from the orders already made.

Such behaviors, however, vary with culture. When Ariely and colleagues ran a similar experiment in Hong Kong, “people who ordered aloud in public would try to portray a sense of belonging to the group and express more conformity.” Cultural differences hint at the interplay between individual motivation and group behaviour. People have competing wants. One of “personal utility” and another of “reputational utility”. Group interactions may result in variety in some situations and herding in others.

The violinist in Washington

Ariely points to another experiment that journalist Gene Weingarten ran with world-class violinist Joshua Bell. The pair wondered what might happen if Bell posed as a busker in Washington, D.C. during rush hour. But after playing for just under an hour at L’Enfant Plaza Station, “only 7 [individuals] (0.5 percent) stopped to listen for more than a minute.” Bell had made only 32 bucks. For context, tickets to see Bell at the New York Philharmonic can cost up to $300 for decent seats.

“When interviewed, passersby said either that they didn’t notice the music at all, or that it sounded like a slightly better than average street performer”, Ariely notes. “No one expected a world-class musician to be playing technically dazzling pieces in a Metro station.” Obviously, this is not a rigorous scientific experiment. Washingtoners are busy getting to work in the morning; and only a fraction of them are likely to appreciate violin concertos. But the point stands. Context and expectations matter.

“Bell [says] that it takes an appropriate setting to help people appreciate a live classical music performance—a listener needs to be sitting in a comfortable, faux velvet seat, and surrounded by the acoustics of a concert hall. And when people adorn themselves in silk, perfume, and cashmere, they seem to appreciate the costly performance much more.”

So, the next time you attend a symphony or art gallery, ask yourself this: how much of your enjoyment do you attribute to personal inclination versus external expectations? Do you agree, for instance, that the Mona Lisa painting or Romeo & Juliet play are beautiful works of art? But what sets it apart from the millions of works that fade into obscurity? Is it the reputation of Leonardo da Vinci and William Shakespeare? Or the legions of academics and high school teachers that tell us how we ought to think about them?

As Ariely writes, “we don’t really understand the role of expectations in the way we experience and evaluate art, literature, drama, architecture, food, wine—anything, really.” When you stop to think about it, everything seems to be rather arbitrarily coherent.

Predictably human

Again, all of this suggests that we have less control and agency than we’d care to admit. Sure, we’re smarter than slugs and dogs. But the economic and social machines in which we navigate are also many times more complex. “We are pawns in a game whose forces we largely fail to comprehend”, says Ariely.

Does that make us predictably irrational? Well, that depends on your frame of reference. After all, even the rational models of economics are laden with wild and arbitrary assumptions. Behavioral economics, likewise, is still in its early days. For one, many of its experiments are contrived; and many of their test subjects are beer-chugging, campus-living college students.

But as economist Andrew Lo writes in Adaptive Markets, “we humans are not so much the rational animal as we are the rationalizing animal.” I’d say then that we are not so much predictably irrational but predictably human. (That does not, of course, deny our unlimited capacity for stupidity.)

“We usually think of ourselves as sitting in the driver’s seat, with ultimate control over the decisions we make and the direction our life takes; but, alas, this perception has more to do with our desires—with how we want to view ourselves—than with reality… Our natural tendency is to vastly underestimate or completely ignore this power… The resulting mistakes are simply how we go about our lives, how we “do business.””

Dan Ariely. (2008). Predictably Irrational.

Sources and further reading

- Ariely, Dan. (2008). Predictably Irrational: The Hidden Forces That Shape Our Decisions.

- Weingarten, Gene. (2007). Pearls Before Breakfast: Can One of the Nation’s Great Musicians Cut Through the Fog of a D.C. Rush Hour?

Latest posts

- The Trusted Advisor — David Maister on Credibility and Self-Orientation

- How We Learn — Stanislas Dehaene on Education and the Brain

- Catching the Big Fish — David Lynch on Creativity and Cinema

- Donald Murray on the Apprentice Mindset and Return to Discovery

- The Hidden Half — Michael Blastland on the Unexpected Anomalies of Life

- Artificial Intelligence — Melanie Mitchell on Thinking Machines and Flexible Humans

- Fallibility and Organization — J. Stiglitz and R. Sah on Hierarchies and Polyarchies

- The Art of Statistics — David Spiegelhalter on Reasoning with Data and Models

- Chess Vision and Decision-Making — Lessons from Jonathan Rowson

- The Drunkard’s Walk — Leonard Mlodinow on Randomness and Reasoning