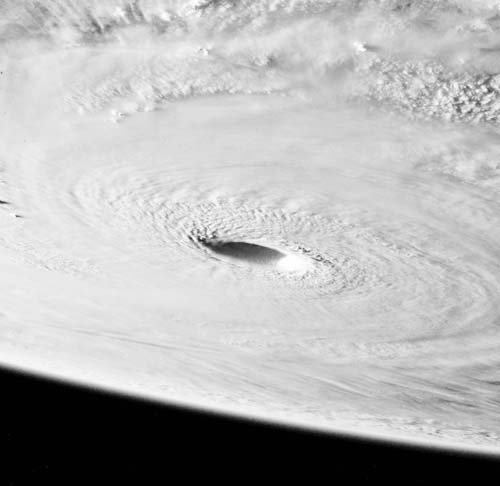

What is going on here? I don’t know!

Households, businesses or governments rarely make optimal decisions. People don’t have the information or capacity to consider, compute and compare every reasonable option. Instead, we tend to make ‘satisfactory’ decisions in incremental steps. Those who believe they’re optimising are probably ignoring some aspect of their uncertainty, assumptions and beliefs.

As John Kay and Mervyn King write in Radical Uncertainty: Decision-making for an Unknowable Future, the important question to ask is “what is going on here?”. Sometimes we get too caught up on the day-to-day minutia to stand back and see the bigger picture. More often than not, the correct answer to that question is “I don’t know”. Great decision makers know what they know and don’t know. They strive to reduce their ignorance.

Skip ahead

- What is going on here? I don’t know!

- The edges of reasoning

- The ivory tower and intellectual failings

- Non-stationarity and reflexivity

- Evolutionary, axiomatic and bounded rationality

- Narrative reasoning and rational deliberation

- A Kay and King way forward

- Legendary investors and decision makers

Knight and Keynes

Kay and King distinguish between uncertainty that is knowable (resolveable uncertainty), and uncertainty that is not (radical uncertainty). The authors paraphrase economist Frank Knight, who said that if risk has a measurable uncertainty, then it isn’t really uncertain at all. John Maynard Keynes also said it important to recognise the ‘uncertain knowledge’ that we cannot attach probabilities to. These are situations in which “we simply do not know”. While risk has a “knowable probability distribution”, uncertainty does not.

Radical uncertainty

“Whatever the playwright of the universe intended, we actors are faced with uncertainty, either because of our ignorance or because of the changing nature of the underlying processes”.

John Kay and Mervyn King, Radical Uncertainty, 2020

“Uncertainty is the result of our incomplete knowledge of the world”, the authors remind. Radical uncertainty manifests itself in many “dimensions: obscurity, ignorance, vagueness, ambiguity, ill-defined problems, and a lack of information”. While it may / may not be a game of chance, we just don’t know what might happen.

Radical uncertainty is akin to the “unknown unknowns” and the “black swans” that we could never foresee. It also pertains to “known unknowns”, like the probability of nuclear annihilation. These events are beyond the reach of probabilistic reasoning, so we describe them with narratives instead. The authors say it’s wise to distinguish between the knowable and unknowable.

Obama’s dilemma

It’s helpful to differentiate between the ordinal and cardinal. That is, there are some events that we can describe in absolute terms (cardinal), and others only in relative terms (ordinal). The authors also observe how we tend to substitute probabilities with descriptions of likelihood and confidence. While this is fine in some cases, it helps to know what we’re really talking about.

Kay and King point to Barack Obama’s tenure as POTUS as one example. They described how counter-terrorism intelligence would supply Obama with tactical options and their probabilities of success. But these probabilities were nothing more than subjective descriptions of their confidence, and a disguise for uncertainty. Kay and King says it’s helpful to distinguish between “assertions of confidence or belief”, and objective likelihood on a “scientific basis”. It’s important to verify your sources too (obviously).

The edges of reasoning

Kay and King probe the blemishes of probabilistic reasoning with several examples. For instance, the Boy or Girl Paradox show how our solutions to questions of probability can vary widely, even for simple problem statements that appear innocuous at first glance. Similarly, the Linda Problem highlights common mistakes in judging the probability of joint-events, while the Two Envelopes Problem show how application of simple probabilities can sometimes lead to nonsensical strategies.

The perfect game of chess

Yes, there are proper solutions to each of the problems above. Their errors or paradoxes arise from a misspecification, misinterpretation and/or miscalculation of the problem itself. But if common trappings exist in ‘simple’ problems, what remains hidden in complex questions that quants and decision makers try to model today? To cite one of my favourite passages from Radical Uncertainty:

“If neither Magnus Carlsen nor Deep Blue can play a perfect game of chess, it stretches the imagination to suppose that ordinary people and businesses could optimise the game of economic life”.

John Kay and Mervyn King, Radical Uncertainty, 2020

A random walk down Wall Street

Our hubris towards uncertainty downplays the challenge of prediction. This reminds me also of Burton Malkeil’s A Random Walk Down Wall Street, in which the author outlined four common errors in prediction: (1) unknowables and unintended consequences; (2) poor data and accounting; (3) analytical and/or computational error; and (4) incentives and biases. These elements demonstrate how easy it is to make forecasting errors. As Kay and King put it, “the probability derived from the model has to be compounded with the probability that the model is itself true”.

The ivory tower and intellectual failings

‘If economists wished to study the horse, they wouldn’t go and look at horses. They’d sit in their studies and say to themselves, “What would I do if I were a horse?”’

Ely Devons

Kay and King remind us that the “intellectual failures of optimising models” contributed to the financial crisis of 2007-08. Their failure to anticipate the crisis was not due to incompetence or motivated reasoning, but in their inability to distinguish between the knowable and unknowable. Many believed that they had conquered the problem of risk and that this time was different. The failure of Long-Term Capital Management, as Kay and King puts it, was due to their faith in models and sense of infallibility. How many times have we heard some forecaster describe a prevailing crisis as a six sigma event?

Physics envy

“Modern economics has lost a great deal in seeking to imitate Planck rather than Keynes”.

John Kay and Mervyn King, Radical Uncertainty, 2020

Kay and King also raise the cost of ‘mathiness’ and ‘physics envy’ in fields like economics and finance. As a former economist myself, I often warned colleagues and clients of their overconfidence in ‘sophisticated’ techniques to model complex social systems. Our models, variables and relationships are often more vague, ambiguous and tenuous than we’d like them to be. Likewise, academic economics and quantitative finance have at times strayed too far from reality, locked away in their ivory tower and axioms. For example, if we assume events are normally distributed, but are in reality governed by power laws, then we’re likely to experience more outliers than our models expect.

The nature of uncertainty

When it comes to decision making under uncertainty, the authors want us to keep three ideas in mind: (1) non-stationarity; (2) evolutionary rationality; and (3) narrative reasoning. We’ll look at each in brief detail, starting with non-stationarity.

Non-stationarity and reflexivity

“Probabilities become less useful when human behaviour is relevant to outcomes”.

John Kay and Mervyn King, Radical Uncertainty, 2020

Unlike the fundamental laws in physics, the ‘rules’ that describe the behaviour of social systems are non-stationary in nature. The probability distribution of outcomes can change over time as people respond to the trends, events and processes that preceded it. Sometimes ideas and “expectations have a life of their own”.

There is also the idea of reflexivity in social systems, which the authors believe is best reflected in Charles Goodhart’s ‘law’. To paraphrase Kay, King and Goodhart: any “policy which assumed stationarity of social and economic relationships [is] likely to fail because its implementation would alter the behaviour of those affected”.

Interestingly, Karl Popper and Robert Merton were among the earliest to discuss the ideas behind reflexivity in great detail. George Soros, a student of Karl Popper, made reflexivity central to his understanding of markets, and his investing philosophy. Soros has written several essays on reflexivity, fallibility and uncertainty as well.

NASA and the Federal Reserve

So, it’s imprudent for example to expect the same predictive power in central banking tools to that of astrophysics. For example, the orbit of celestial bodies are independent of our attitudes and preferences. Economies by contrast face a higher degree of ambiguity and indeterminacy. Making predictions or expectations public can change the behaviour of the participants that informed it in the first place. To paraphrase the authors, some problems in life are puzzles, while others are non-stationary mysteries.

Adaptive processes

Like the weather and other nonlinear complex systems, social systems are sensitive to initial conditions and the environment. But unlike other physical systems, social systems can adapt with some degree of intentionality. As individuals and groups, we respond to past events and future expectations. And such adaptive processes are everywhere. Think scholarship, entrepreneurship, competitive markets, creative destruction and so on. As Kay and King put it: “Darwin’s ‘dangerous idea’ is key, not just to explaining the origin of species, but to understanding the development of our economy and society.”

The nature of organisation

It’s fascinating (to me at least) to see how people with incomplete knowledge can come together to produce sophisticated things like jet planes, transistors and skyscrapers. For example, communication, coordination, cooperation and learning allows us to utilise and nurture the wisdom of the crowds to achieve the remarkable. Here, the authors point out that “what is valuable is the aggregate [knowledge of the crowd], not the average of its knowledge”.

“For all that has recently been said about ‘the wisdom of crowds’, the authors prefer to fly with airlines which rely on the services of skilled and experienced pilots, rather than those who entrust the controls to the average opinion of the passengers.”

John Kay and Mervyn King, Radical Uncertainty, 2020

So, I think it’s interesting to understand how organisational design and hierarchies enable us to innovate, adapt and navigate uncertainty. Kay and King find it “surprising how little attention has been given to the economics of organisation”.

Evolutionary, axiomatic and bounded rationality

Given our imperfect attention, memory and cognitive functions, we rely on beliefs, biases and heuristics to make decisions. And to navigate complexity and radical uncertainty, we adapt incrementally, not optimally. In these situations, we rely more on inductive and abductive reasoning than deductive reasoning.

Of course, such an approach is sometimes fallible. They can result in systematic and predictable thinking errors. But I’ll omit Kay and King’s discussion here for brevity since we’ve discussed this at length previously. See our posts on Annie Duke’s Thinking in Bets, Daniel Kahneman’s Thinking, Fast and Slow, Robert Cialdini’s Influence, Charlie Munger’s Psychology of Human Misjudgement, and Philip Fernbach’s The Knowledge Illusion.

“Evolutionary rationality gave us the capacity to make computers, but not to be computers”.

John Kay and Mervyn King, Radical Uncertainty, 2020

Bounded rationality

Kay and King offer one warning to books that talk at length about our irrationality: that it’s important to distinguish between axiomatic and evolutionary rationality. For example, economic theories on rational choice often contain strong assumptions about preferences (like completeness, transitivity, continuity and independence). We know that people don’t always conform to these assumptions in real life.

Does that make us irrational? In real world problems, we have to make decisions with a small set of choices, personal beliefs and incomplete knowledge. This is what Herbert Simon referred to as bounded rationality. While our behaviour might seem irrational or suboptimal in an axiomatic sense, they may remain rational in an everyday sense if based on reasonable beliefs and an internal consistency.

Rationally irrational

So, we should be careful not to draw sweeping conclusions about human fallibility and irrationality based on small-world, small-sample models, theories and experiments. Brain teasers, word games and optical illusions that demonstrate our fallibility are not necessarily reflective of our everyday reality. The economist, psychologist or philosopher’s description of rationality might fail outside their ivory tower.

To presume something as ‘irrational’ is to assume we ourselves know what is both rational and reasonable for everyone. It’s not easy to distinguish between differences or errors in reasoning, from differences or errors in beliefs. And yet we tend to think ourselves more objective than others. What folly! Kay and King put it most succinctly:

“Most problems we confront in life are typically not well defined and do not have single analytic solutions… There will be different actions which might properly be described as ‘rational’ given any particular set of beliefs about the world. As soon as any element of subjectivity is attached either to the probabilities or to the valuation of the outcomes, problems cease to have any objectively correct solution.”

John Kay and Mervyn King, Radical Uncertainty, 2020

Narrative reasoning and rational deliberation

Effective communication and coordination is an important element of high-functioning social groups. Kay and King describe how we as social creatures rely on narratives to think, communicate and make decisions. Narratives help us to build networks, hierarchy, culture and complex group functions. Narratives and value judgements are unavoidable, especially when we’re faced with radical uncertainty. To believe otherwise is to mislead ourselves.

Dualism and argument

“The test of a first-rate intelligence is the ability to hold two opposed ideas in the mind at the same time, and still retain the ability to function”.

F Scott Fitzgerald, 1936

Kay and King observe how “devotees of probabilistic reasoning have much to learn from the accumulated wisdom of the practice of law”. The authors highlight the role of credible and coherent narrative reasoning in common law. They discuss the utility of concepts in legal spheres such as ‘preponderance of the evidence’, ‘balance of probabilities’ and ‘beyond reasonable doubt’. The authors highlight a thoughtful message from Anne Marrie Slaughter:

“Thinking like a lawyer also means that you can make arguments on any side of any question. Many of you resist that teaching, thinking that we are stripping you of your personal principles… On the contrary, … [it is] learning that there are arguments on both sides and learning how to hear them…. It is our best hope for rational deliberation.”

Anne-Marie Slaughter, On Thinking Like a Lawyer

Competing narratives

The authors also cite Robert Shiller’s views on the “interplay of competing narratives” in financial economics. In Irrational Exuberance, Shiller describes how contagious narratives can fuel positive or negative feedback loops in financial markets. Kay and King point out how narratives and knowledge, whether right or wrong, can experience its own form of evolution. Malcolm Gladwell offered a similar view in The Tipping Point.

With this lens, Kay and King define risk as the probability of “failure of a projected narrative, derived from realistic expectations, to unfold as envisaged”. And so to manage risk, we must first understand our reference narrative. This, in the authors’ view, helps to explain why people pay insurance. They aren’t computing their individual expected value. Instead, it’s the comfort in knowing that their reference narrative is protected.

“The willingness to challenge a narrative is a key element not only in scientific progress but in good decision-making.”

John Kay and Mervyn King, Radical Uncertainty, 2020

A Kay and King way forward

Radical uncertainty, non-stationarity, ivory towers and the edges of reasoning makes prediction and good decision making difficult. But Kay and King offer some practical ways forward. I summarise my favourite here: (1) Bayesian dials; (2) Plumbing tools; and (3) Good enough.

Bayesian dials

One useful idea is what Kay and King refer to as the ‘Bayesian dial’. The idea of a one’s Bayesian dial is to think about the preconceived probabilities we attach to problems and expectations. The dial is meant to remind us about the consequences of conditional probability and Bayes’ theorem, as new evidence comes to light.

While we’re unlikely to bring well-tuned Bayesian dials to every problem due to incomplete information, resource constraints, radical uncertainty, its philosophical premise remains valid. That is, good decision makers update their Bayesian dial and prior probabilities as they receive new and reliable information.

Kay and King tells us to watch for ideology, arrogance, grand theories, universal explanations and our own limitations. As the authors put it, “in the ordinary business of life, where we are constantly confronted with unique situations, we need a pluralism of approaches and models.” Effective decision-makers, “listen respectfully, and range widely to seek relevant advice and facts before they form a preliminary view”. This is reminiscent of other great minds, like Charlie Munger and Edward Thorp, who think in mental models and probabilities.

Plumbing tools

In business, we should use simple models to think about the factors that matter. Kay and King remind us that models are small world descriptions. Adding more factors and complexity may not improve its predictive power or representation of reality. Similarly, we should consider the trade-offs between insight and effort. Simple models may give us more time to think about our inputs, assumptions, alternatives, knowledge and radical uncertainty.

I’m also reminded of Richard Feynman‘s observation about the philosophical and psychological consequences of theories. Different approaches to the same problem will influence the way we think. Just compare and contrast the behaviour of practitioners that see their craft as blunt, incomplete and fallible instruments to those that believe they’ve found a general theory of biosocial choice. As Kay and King put it:

“Models are tools like those in the van of the professional plumber, which can be helpful in one context and irrelevant in others”.

John Kay and Mervyn King, Radical Uncertainty, 2020

Iteration (or good enough)

Kay and King encourages readers to consider an ‘evolutionary’ approach to decision making. That is to make choices that we believe can improve our position incrementally under both knowable and unforseen circumstances. This is in contrast to decision making frameworks that seek to optimise one’s position based on strong expectations about future states. Again, we have to consider the cost-benefit trade-off between what is ‘optimal’ and ‘good-enough’.

Legendary investors and decision makers

Finally, Radical Uncertainty reminds me of the divisions people draw between fundamental and technical analysis in investing. The former usually looks at business attributes that are conducive to enduring value creation, while the latter draws from indicators and abstractions to make inferences about mispricing, and/or the direction of entire systems. Both models have their proponents, detractors and track records of course.

What’s also interesting about it is what it reveals about us. What we think is knowable and predictable will guide our choice of methods for research, analysis and interpretation. This choice also tells us something about our underlying beliefs, assumptions and evidence about complex systems. How confident are we that our chosen method is sound? Why? What does the other practitioner see that we don’t?

Regardless, there appears a common thread among great investors and decision makers. They understand the nuances of probability, risk and uncertainty. They distinguish between the resolvable and radical, the knowable and unknowable, and apply probabilistic reasoning in practical ways. (For the interested, I recommend Mohnish Pabrai’s The Dhandho Investor, Howard Mark’s Mastering the Market Cycle, and Charlie Munger’s The Art of Stock Picking as further reading)

Further reading

Kay and King drew from a rich source of knowledge to write their book. I highlight the authors that caught my eye:

- Daniel Kahneman. (2011). Thinking, Fast and Slow.

- Annie Duke. (2018). Thinking in Bets: Making Smarter Decisions When You Don’t Have All the Facts.

- Robert Shiller. (2000). Irrational Exuberance.

- Richard Rumelt. (2011). Good Strategy Bad Strategy: The Difference and Why it Matters.

- Blaise Pascal and Pierre de Fermat. (1654). Translated Correspondence on Probability.

- Jerome Groopman. (2007). How Doctors Think.

- Charls Mackay. (1841). Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds.

- Lewis Carroll. (1871). Through the Looking-Glass.

- Thomas Davenport & Brook Manville. (2012). Judgment Calls.

References

- John Kay and Mervyn King. 2020. Radical Uncertainty: Decision-making for an Unknowable Future. <More articles from John Kay: https://www.johnkay.com/articles/>

- Burton Malkiel. (1973). A Random Walk Down Wall Street: Including a Life-Cycle Guide to Personal Investing.