Malcolm Gladwell’s tipping points

Understanding how social complex systems interact can help us to make more informed decisions in business (e.g. understanding consumer fads or market behaviours). Drawing inspiration from epidemiology, in his book The Tipping Point, journalist Malcolm Gladwell describes the conditions that enable ideas, trends and social behaviours to spread like an epidemic. While his work on occasion draws a little too much from anecdotes and small sample sizes, it provides a simple but useful mental model for analysing the diffusion of ideas, products and innovation. His work is also a nice complement to other books that focus on complex systems. In business and finance, this includes Robert Shiller’s Irrational Exuberance and Howard Mark’s Mastering the Market Cycle. In this post, we’ll review some of the lessons that we drew from Gladwell’s work.

Epidemics and tipping points

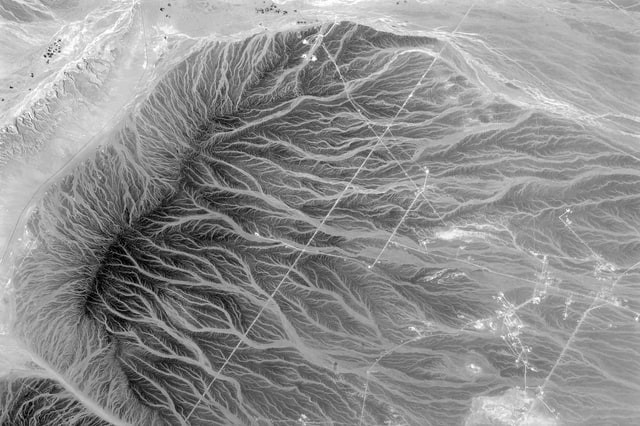

Malcolm Gladwell’s main contention is that ideas, products and behaviours (or agents) behave in similar patterns to infectious diseases. Like epidemics, such agents can be emotionally contagious, where small causes can trigger large and sometimes sudden effects. We do not always appreciate the potential for exponential shifts in beliefs and behaviours due to our inability to grapple with geometric progressions intuitively.

Gladwell also describes his idea of a tipping point, a threshold or critical mass that enables little things to trigger a significant outcome. It is a perturbation that shifts society into disequilibrium, allowing social epidemics to take place (e.g. new ideas, products, etc.). Like infectious diseases, Gladwell believes social epidemics are largely a function of three factors: the people who transmit the agents; (2) the agents itself; and (3) the environmental context.

Trendsetters, contagions and stickiness

Gladwell reveals how successful trendsetters operate. They watch the behaviours of innovators that operate independently or outside mainstream circles. They look for trends that are both contagious and sticky, and how pervasive they are in contemporary culture like film and fashion. This might signal a tipping from niche to mainstream. Gladwell also introduces a concept early in his book that he calls the ‘law of the few’. It describes the people best placed to transmit new ideas, products, innovations and behaviours contagiously. Whether messages or agents tip in favour depend often on the characteristics of the messenger. Not all individuals are well placed to spread new ideas effectively.

Connectors, mavens and salespersons

The author suggests that there are three types of personalities that can transmit (infect) at relatively high rates: (1) Connectors, (2) Mavens and (3) Salesperson. The most ‘contagious’ people may possess two or more of these personality traits. Their descriptors are relatively self-explanatory. Connectors are individuals with large social networks. They are specialised at making friends and connecting people. Their gravity and networks improve the likelihood and degree of transmission.

Mavens on the other hand are information specialists or accumulators of knowledge. Gladwell describes them as information brokers that are motivated by curiosity and a social desire to help their networks make better decisions. While their social circles are smaller than connectors, they are often trusted or influential sources in the marketplace. Finally, we have great salespersons, charismatic individuals who are effective in persuading us of one thing or another. The author highlights how great salespersons are master storytellers, knowing which details to sharpen or level.

However, Gladwell suggests that some trends emerge, and others don’t due to sheer happenstance. That is, the idea did not find enough connectors, mavens and/or salespeople to proliferate the idea, product or behaviour.

Contagiousness and stickiness

Gladwell reminds readers that it is helpful to distinguish between the contagiousness and stickiness of an idea, product or behaviour. Even with highly ‘infectious’ individuals, social epidemics are unlikely to take place without sticky agents. This refers to the quality of the product, memorability of the message or benefit of an innovation. However, Gladwell believes that the line between an agent’s success or failure is sometimes very thin. The way we package, present and repeat a set of messages can have significant impact on its stickiness. The author provides several case studies to support this, which we exclude here for brevity.

The power of context

While social epidemics depend largely on the agent’s transmission rates and stickiness, environmental conditions at the time may help or hinder its spread. For social epidemics to gain momentum, it often depends often on many small factors acting favourably in the same direction.

Continuities and equilibriums

Furthermore, the author emphasises our desire to maintain coherence and continuity in our perception of the world and events. This is well documented in books such as Daniel Kahneman’s Thinking, Fast and Slow. Both Kahneman and Gladwell suggest that our personalities and logical systems are not as consistent as we would like to believe. Our habits and tendencies are very much context dependent. Gladwell notes that we don’t observe this often because we are usually quite adept at maintaining consistency in our environment and personal narrative. However, change the context and social equilibrium, and new collective behaviours can emerge rapidly, unpredictably and at scale.

Communities, networks and peer pressure

Gladwell also emphasises the power of peer pressure and social norms that shape our behaviours. He describes for example how highly charismatic evangelists bring change in people’s beliefs by creating communities to nurture such expressions. Small communities can be effective in reinforcing behaviours and magnifying peer pressures. However, Gladwell suggests that we begin to reach our intellectual and emotional capacity as groups cross the size of 150. In these cases, more complex hierarchies or structured clusters are needed to organise behaviours.

Innovators and laggards

It is also this interconnectedness of different social networks that enable ideas, innovations and behaviours to spread. Big movements often emerge from multiple smaller movements. Gladwell suggests that this is reminiscent of epidemic curves we see in technology diffusion and social movements. In the former example, technology migrates from the innovators and early adopters to the majority and laggards. The degree of communicative disconnect between the four groups can affect the pace of innovation diffusion. From this, we can see how agent’s contagiousness (e.g. connectors), stickiness (e.g. novelty) and context (e.g. economic conditions) come into play.

Irrational exuberance

Economist Robert Shiller shared a similar view to Gladwell in that epidemiology models are useful for studying the spread of ideas. This applies to financial markets as well by extension. Shiller describes in his book Irrational Exuberance how the combination of greed, financial experts (mavens & salespersons), social proof and the fear of missing out can enable investment fads to flourish. This can create a naturally occuring Ponzi scheme. This is where an initial increase in asset prices translates to an improvement in expectation, further fuelling demand, prices, expectations and so on.

The tipping point occurs when the majority join the fray and the news media reinforces the narrative. During these spells, people will justify their behaviours with arguments that this time is different. However, as financial history would tell us, such behaviours today are likely no different from decades or centuries past. From the tulip mania in 1637, to the Dot Com Bubble of the late 1990s, we can see how easy it is under the right conditions for ideas and fads to spread like wildfire.

Further reading

- Mastering the Market Cycle – Howard Marks

- Irrational Exuberance – Robert Shiller on stock market manias

- Thinking, Fast and Slow – Daniel Kahneman on choices, biases and heuristics

- This Time is Different – Reinhart and Rogoff on financial crises

References

- Gladwell, M (2000). The Tipping Point: How Little Things Can Make A Big Difference. More at <https://www.gladwellbooks.com/>

- Shiller, R. (2000). Irrational Exuberance. More details available at <http://www.econ.yale.edu/~shiller/>