Embedded in nature

It is tempting to think of ourselves and our species as something separate from nature—that we’ve somehow jumped the system through this ferry we call culture and technology. But as Lewis Thomas reminds in The Lives of a Cell, such a thought “is an illusion.” For all our skyscrapers, rockets, vaccines, computers, and satellites, we are forever “embedded in nature.”

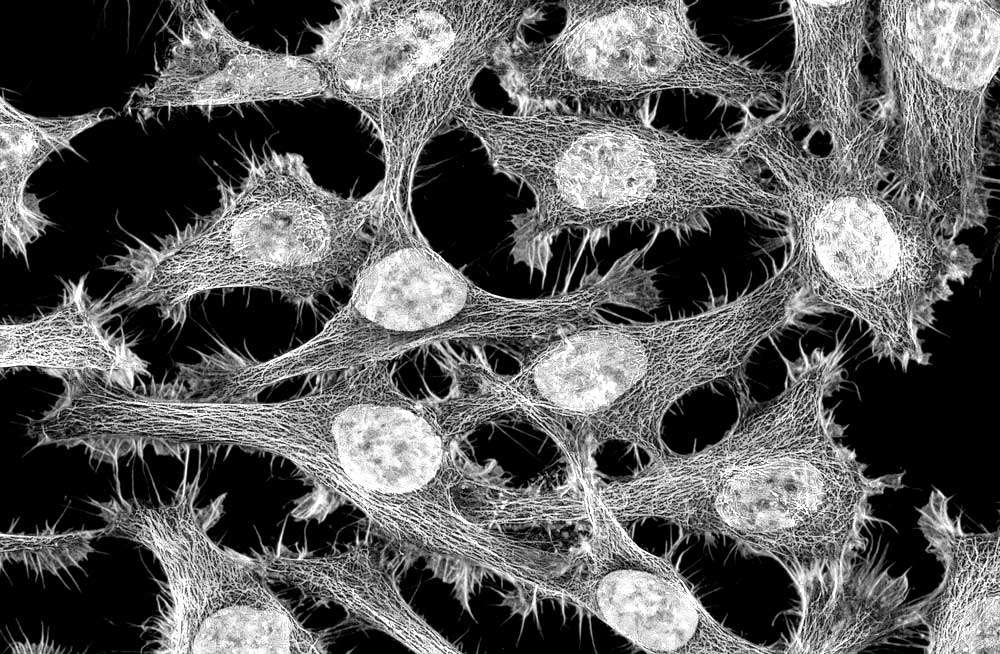

On one level, we are not the ‘self’ or ‘I’ that we conceive in an everyday sense. We are not made whole by tiny parts of ourselves. Rather, we are as Thomas puts it: “shared, rented, and occupied.” Inside our cells, for instance, are primeval partnerships with curious organelles that biologists affectionately call mitochondria. You see, mitochondria are the “power plants of the cell”, but they live rather separate lives—maintaining and replicating themselves independently. They even house their own genome. And “without them, we would not move a muscle, drum a finger, [or] think a thought.”

The story is similarly true for plants and chloroplasts. Like mitochondria, chloroplasts live in the cells of plants with genomes of their own. Through photosynthesis, they take in sunlight, carbon dioxide, and water to make sugars for plants and animals, and the oxygen we breathe. We might even say that much of modern life owes its existence to such “ancient symbiosis”.

Agglomerative tendencies

Zoom out and we see something else altogether. Millions of us, everyday, scurrying from home to office and office to home—forever coalescing, reassembling, and separating. We make families, farms, clubs, corporations, churches, empires, and everything in between. From a distance, these motions and collisions look nearly autonomous. And one cannot help but see the parallels to the social insects. Thomas agrees, going as far to say that “ants are so much like human beings as to be an embarrassment.” After all, “they farm fungi, raise aphids as livestock, [and] launch armies into wars.” “ They do everything but watch television.”

There is something to be said about agglomeration here. In nature, there is the “joining of organisms into communities, communities into ecosystems, and ecosystems into the biosphere.” In society, we turn cities into states, states into nations, and nations into alliances. Indeed, people, herrings, and starlings are all rather plain by their lonesome. But once critical mass is reached, their institutions, shoals, and murmurations are entities to behold. For “it is in our collective behavior that we are most mysterious”, Thomas writes.

Assembly and hierarchy

What we should look for then is the way in which assembly and hierarchy reforms the group and its constituents. “Single locusts”, for example, “are quiet, meditative, sessile things”, Thomas notes. But “when there are enough of them packed shoulder to shoulder, they vibrate and hum with the energy of a jet airliner.” Most species of ants, by contrast, are so tightly integrated that any lone worker is doomed if it were to find itself separated. “Ants are more like the parts of an animal than entities on their own”, says Thomas. “Mobile cells, circulating through a dense connective tissue of other ants in a matrix of twigs.”

Perhaps we humans are just as interlocked. Culture and technology make it so. Sever us urbanites from the electrical grid, sewage systems, supply chains, work clusters, and the world wide web, and chaos surely ensues. Human impulse in our scramble for subsistence would indeed be frightening. Humanity would go on, of course. Just not in the manner or scale that we’ve grown accustomed to. We are, for better and worse, embedded and indebted to each other in a shifting house of cards.

Living languages

Ecosystems, assemblies, and hierarchies are everywhere, even in the unseen. Take language, for instance. Like the cells in our bodies or the termites in colonies, there is something autonomic about the way speech and language comes together. Within every word and expression are complex rules, deep structures, and rich histories—more complicated than that of arithmetic. It is an amorphous collection of informal agreements that millions of people share.

Yet, somehow it all works. Hidden relay runners in our minds seem to find the words and sentences we need without too much fuss. More than that, “language is simply alive”, says Thomas. It grows and evolves. We tend to it in our tiny pastures like a blind gardener. Words, phrases and meanings join, mutate, and split apart—selected for under the pressures of human affairs.

I guess if we abstract far enough, every system appears analogous. Thomas, for one, suggests that there is an “essential wildness of science as a manifestation of human behavior [that] is not generally perceived.” Blur your vision enough and even scientists begin to look like ants. Compelled by the urge of discovery and knowing, they obsess over peculiar trails and signals.

This swarm of exploration may at times appear disorderly, chaotic even—full of false starts, wrong turns, and beautiful blunders. Yet again, like the miracle of language, something coherent emerges from the formless. An invisible, insatiable body of knowledge that Thomas believes “to be under the influence of a deeply placed human instinct.”

A buzzing biosphere

If we zoom out even further now, what we see is a buzzing biosphere. One teeming with seen and unseen ecosystems, each of tremendous depth and complexity. Each participating in an interlocking exchange and assembly of information. Of course, “evolution is still an infinitely long and tedious biologic game, with only the winners staying at the table”, Thomas writes. “But the rules are beginning to look more flexible.” We ourselves are embedded and evolving everywhere. Not only with our mitochondrial friends and other tiny critters inside us, but with language, science, and other imaginary systems we conjure for ourselves—drawing in everything we can from nature and the sun to pursue our own complex ends.

As Thomas writes:

“I have been trying to think of the earth as a kind of organism, but it is no go. I cannot think of it this way. It is too big, too complex, with too many working parts lacking visible connections. The other night, driving through a hilly, wooded part of southern New England, I wondered about this. If not like an organism, what is it like, what is it most like? Then, satisfactorily for that moment, it came to me: it is most like a single cell.”

Lewis Thomas. (1974). The Lives of a Cell.

Sources and further reading

- Thomas, Lewis. (1974). The Lives of a Cell.

- Krugman, Paul. (1995). The Self Organizing Economy.

- Dyson, Freeman. (1988). Infinite in All Directions.

- Ferris, Timothy. (1992). The Mind’s Sky.

Latest posts

- What’s Eating the Universe? Paul Davies on Cosmic Eggs and Blundering Atoms

- The Dragons of Eden — Carl Sagan on Limbic Doctrines and Our Bargain with Nature

- The Unexpected Universe — Loren Eiseley on Star Throwers and Incidental Triumphs

- Bridges to Infinity — Michael Guillen on the Boundlessness of Life and Discovery

- Ways of Being — James Bridle on Looking Beyond Human Intelligence

- Predicting the Unpredictable — W J Firth on Chaos and Coexistence

- Order Out of Chaos — Prigogine and Stenger on Our Dialogue With Complexity

- How Brains Think — William Calvin on Intelligence and Darwinian Machines

- The Lives of a Cell — Lewis Thomas on Embedded Nature

- Infinite in All Directions — Freeman Dyson on Maximum Diversity