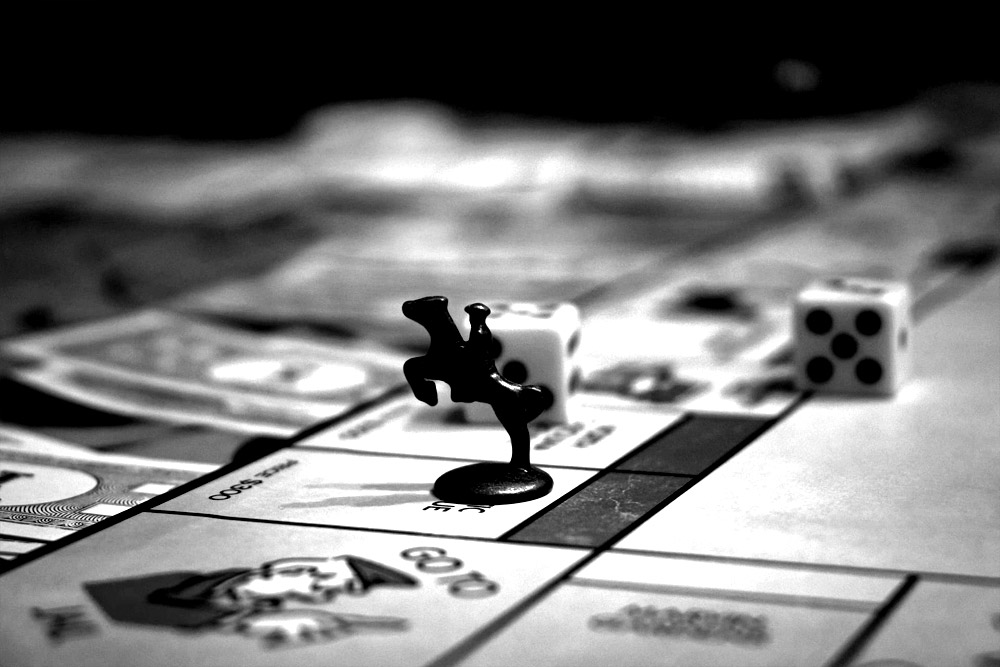

A microcosm in Monopoly

Monopoly is a maddening but illustrative board game. While everybody begins with equal cash-in-hand and good vibes, the game almost always descends into imbalance, anarchy, and petty squabbles.

Whether by skill or luck, somebody will get a head start. That one extra property turns into two, then into three, and so it goes. Eventually, the plebian majority find themselves fighting for scraps as the newly crowned monopolist steamrolls his or her way to victory. What’s more, the winner feels smug, forgetting the lucky rolls that came his or her way.

The Matthew Effect

Monopoly, you see, is a microcosm of what the sociologist Robert Merton calls the Matthew Effect. The effect describes the tendency for early advantages to accumulate over time.1 Society is no stranger to this phenomenon, of course. Our language is littered with sayings like ‘the rich get richer while the poor get poorer’. Intuitively, people know that advantage begets advantage.

[1] Merton took the name ‘Matthew’ from the Gospel of Matthew (13:12), which said: “for whosoever hath, to him shall be given, and he shall have more abundance: but whosoever hath not, from him shall be taken away even that he hath.”

Snowballs, scientists, and artists

As the sociologist Daniel Rigney explains, the Matthew Effect arises in social systems in which “initial advantages are self-amplifying.” They’re “like the proverbial snowball that grows larger as it rolls down a hillside.” Famous scientists, for example, find it easier than unknown scientists to publish and disseminate their works. Their past achievements endow them with a cult following, media attention, and the halo effect.

The effect is even more pronounced in the arts, where selection mechanisms are less meritocratic and more subjective. Indeed, why do some abstract paintings trade at enormous sums while others fade into obscurity? (Mark Rothko’s painting of two rectangles, for example, sold for a cool $31 million.)

Bandwagon effects and Justin Timberlake

We can find similar bandwagon effects in sports and politics too. As self-conscious, social creatures, people derive comfort from the crowd, especially when the crowd is ‘winning’. Popular athletes and presidential candidates tend to, by virtue of popularity, attract even more supporters.

In one experiment, Duncan Watts and colleagues asked 14,000 people to listen to and rate music by bands that they had never heard of before. While the control groups could see the name of the song and the band, the test groups could also see the number of times the song was downloaded.

Now, if music preferences were independent, you’d expect similar ratings between the control and test groups. The researchers found, however, that the test group tended to rate popular songs more favorably than the control-group who had zero knowledge of public opinion. Their study reveals how our preferences are shaped by others. In the social world, popularity begets popularity.

Wall Street and Silicon Valley

Matthew effects are just as pervasive in business. We have all heard the clichés: “it takes money to make money”; “the first million is the hardest”; and “success begets success”. Indeed, the dual arm of compound interest and inherited advantage, for starters, will make the wealthy wealthier.

This is often inherent in the structures of competition too. Enterprises with scale economies, network effects, high-switching costs, increasing returns, or cartel-like associations can use their advantages to further their advantage. So it should come as no surprise that many industries, from computing to finance, are today dominated by large oligopolies. Facebook and LinkedIn, for example, dominate their respective niches because they enjoy majority market share. And everybody uses their platforms because everybody else is using it too. In the world of social media, users beget users.

Superhubs like Wall Street and Silicon Valley benefit similarly from their own type of “circular causation”. As economist Paul Krugman explains, “people and businesses locate there because of the opportunities created by the presence of other people and businesses.” “Market forces”, Rigney adds, “tend to attract and concentrate capital, skilled labor, and other resources in favored central locales.” The same can be said about our top-ranking universities. Their reputation and success are sustained in part by the talent and investment that their reputation and history attracts. Here, prestige begets prestige.

Brain drain and poverty traps

But the Matthew effect operates in reverse as well. People who cannot access food, water, housing, and healthcare will not be able to work. And those who cannot work cannot pay for the necessities that allow them to work. Similarly, when the nation does not generate enough output, it will not collect enough taxes to pay for public works that families need to be productive. Brain drain and capital flight, in turn, subtracts further from the nation’s productivity and potential—adding further to the nation’s woes.

Countervailing forces

Each of these examples exhibit a “circular and cumulative causation”—a positive feedback loop not unlike the screeches of a microphone-loudspeaker tandem. From strength to strength, or weakness to weakness, society has to contend with virtuous and vicious cycles.

That’s not to say, however, that Matthew effects are deterministic or ‘locked-in’ once underway. After all, nothing grows or persists forever. Countervailing forces may arise to curb or reverse such self-amplifying effects.

Nineteenth century economists like Thomas Malthus, for example, once worried about the economic and social dangers of population explosions. But what they did not foresee was the dampening effects of birth control and the shift towards smaller families that took place during the twentieth century.

Many economists and politicians today, by contrast, mistake the economy for a perpetual machine. Invention begets invention, just as growth begets growth, they’ll say. But as we’ve seen over the course of geologic time, nature certainly has its limits and a penchant for calamity.

Similarly, in market economies, Matthew effects are often eroded by “the vicissitudes of competition” and creative destruction, Rigney reminds. “No amount of initial advantage can save an individual, firm, or nation from the perils of disastrous errors in judgment.” The old makes way for the new. In society, government intervention, social movements, and populous revolts are often necessary to reverse entrenched Matthew effects. Rigney points, for example, to “the slave rebellions of ancient Rome… through [to] the French Revolution.”

Opportunity structures and American mythmaking

Clearly, reversing vicious cycles is anything but easy. Indeed, despite our protracted struggles, from the civil rights movement to the feminist movements, many injustices and inequalities of the past persist to this day. In many ways, social and economic life “resembles [a] skewed Monopoly game”, Rigney notes. “Some are born into vast fortunes, while others are born into famine.” While we all have chances to succeed, we do not all have an equal opportunity to succeed.

Yet American society continues to “embrace the cultural myth of the self-made man, as though any of us could create ourselves in a social vacuum.” They underplay the ever present role of luck and cumulative causation on the grand stage.

The issue is plain as day in education. Children who fall behind in reading tend to avoid the subject in frustration, which feeds further into their difficulties. “Mutually reinforcing problems”, like a troubled homelife, underfunded classrooms, and hungry stomachs, can compound the issue. Through no fault of their own, opportunities for these children narrow as the disparities in their lives widen.

What’s more, the interplay between cumulative advantage and social influence makes our systems inherently sensitive to its own history. Would J.K Rowling, the author of the Harry Potter series, be as successful as she is today if we rerolled history? You may recall, for instance, that more than a handful of publishers had rejected Rowling’s manuscript before her runaway success. But what if she was rejected by twenty, thirty, or fifty publishers? At some point, economic reality must set in. There are probably countless authors-in-waiting, not unlike Rowling, who never see the light of day.

Indeed, these are wicked problems that we cannot resolve in a single sitting. But “a wider awareness of Matthew effects and their potentially destructive and constructive consequences”, Rigney notes, “can raise the quality of public discussion.” If we can uncover the hidden structures, social mechanisms, and feedback loops that underpin our systems, then maybe we can cultivate more virtuous cycles for all.

Sources and further reading

- Rigney, Daniel. (2010). The Matthew Effect: How Advantage Begets Further Advantage.

- Watts, Duncan. (2007). Is Justin Timberlake a Product of Cumulative Advantage?

- Krugman, Paul. (2001). Can Injured New York Recover Completely?

Latest posts

- Arguing with Zombies — Paul Krugman on Bad Models and False Idols

- Raghuram Rajan on Financial Development and the Making of a Riskier World

- The Winner’s Curse — Richard Thaler on the Anomalies of Auctions

- The Market for Lemons — George Akerlof on Asymmetry, Uncertainty and Information

- Reflexivity and Resonance — Beunza & Stark on Quantitative Models and Systemic Risk

- Power Laws — Mark Newman on Solar Flares, Gambling Ruins and Forest Fires

- Heresies of Finance — Benoit Mandelbrot on Volatile Volatility and Valueless Value

- Financial Instability Hypothesis — Hyman Minsky on Ponzi Finance and Speculative Regimes

- Constructing a Market — MacKenzie and Millo on Performativity and Legitimacy in Economics

- The Wrong Track — Benoit Mandelbrot on the Future of Finance