Financial astrology

The finance industry manages risk in seemingly contradictory ways. Technical chartists, for example, believe that buy and sell signals are self-evident in the price, volume, and related data sheets that they peruse. Colorful parlance, from rectangle patterns to triple tops, are used to describe what they see. Fundamentalists, on the other hand, believe such financial astrology to be hogwash. They prefer instead to focus on first principles and valuation to identify mispricing.

Modern finance emerged not long after, giving business schools something mathematical to teach. It began in the early 1900s when Louis Bachelier studied the random walks in financial markets—suggesting that security prices jump about randomly, much like a toss of a coin. By the 1960s, Eugene Fama, Paul Samuelson, and other economists had pushed the reasoning further and developed the Efficient Market Hypothesis. They argued that prices will move in random fashion if markets are efficient.

The theorists believed that technical and fundamental analysis could not beat the market over the long run because prices already reflect all information. And on this backbone, the Capital Asset Pricing Model, Modern Portfolio Theory, Modigliani-Miller Theorem, and Black-Scholes-Merton Model, soon made their way. They endowed Wall Street with new tools and legitimacy. New jargon, like betas, alphas, and volatility, grew to dominate the vernacular.

The wrong track

But as Benoit Mandelbrot laments in The Misbehavior of Markets, “the theorists have been going down the wrong track.” Just recall, for instance, the spectacular blow up of Long-Term-Capital-Management, of which Nobel laureates Myron Scholes and Robert Merton were board directors.

“In the fun-house mirror logic of markets, the chartists [and theorists] can at times be correct.” But if Wall Street is crying black-swan every few years or so, then you know something is off”, writes Mandelbrot. “If you are going to use probability to model a financial market, then you had better use the right kind of probability.”

“As an industry, finance buys more computers than almost any other. It hires a huge proportion of the world’s newly minted math and economics graduates. It is a vast calculating machine… All the academic models are here… [But] the result is something like a traditional medicine or over-the-counter nostrum: many different chemicals and no clear “active ingredient.”

Benoit Mandelbrot and Richard Hudson. (2004). TheMisbehaviour of Markets.

Conservatism and representativeness

For starters, modern finance assumes that people are rational and astute enough to correct mispricing. Arbitrageurs, they assume, will step in to exploit the discrepancy while irrational investors are eliminated by their own underperformance. Efficiency, they suggest, is an inevitable consequence of economic selection.

But behavioral economics tells us that people are predictably irrational. We make routine thinking errors all the time. As Andrei Shleifer highlights in Inefficient Markets, investor conservatism, in which “individuals are slow to change their beliefs in the face of new evidence”, tends to generate underreaction; while representativeness, in which investors “view events as typical or representative… and ignore the laws of probability”, tends to result in overreaction.

What’s more, arbitrage in the real world is often limited because strategies without close substitutes must rely on some eventual correction. The asymmetry of long-short positions and the flow of funds does not help either. Investors and financiers, for example, tend to withdraw during extreme panics, which happens to be the moment when arbitrageurs need to be most active.

Similarly, if mispricing is not quick to self-correct, then irrational investors can persist longer than an efficient market would suggest. Time and time again, pockets of traders will latch on to a new trend, pattern, or theory, no matter how spurious it might seem to be—generating their own reality in turn. Financial bubbles persist in part for this very reason.

“I’m convinced that there is much inefficiency in the market. These Graham-and-Doddsville investors have successfully exploited gaps between price and value. When the price of a stock can be influenced by a “herd” on Wall Street with prices set at the margin by the most emotional person, or the greediest person, or the most depressed person, it is hard to argue that the market always prices rationally. In fact, market prices are frequently nonsensical”.

Warren Buffett. (1984). The Superinvestors of Graham-and-Doddsville.

Heterogeneity and nonlinearity

Moreover, in contrast to standard theory, investors are not identical. People have different goals, preferences, horizons, risk-appetites, and skin-in-the-game. As Mandelbrot explains, “once you drop the assumption of homogeneity, new and complicated things [will] happen in your mathematical models.”

He notes, for example, that in a simple simulation with two investor types—fundamental investors that act on value and technical chartists that trade on trends—market dynamics can evolve unexpectedly. “The market switches from a well-behaved linear system… to a chaotic nonlinear system.” Rallies, bubbles and crashes will come and go. “And that is with just two classes of investors”, writes Mandelbrot. “How much more complicated and volatile is the real market, with almost as many classes as individuals?”

Long memories and volatile volatility

That is to say, markets do not follow the stochastic Brownian motion that Bachelier had previously assumed. In particular, three of its assumptions about price variation—independence, stationarity, and the bell curve—do not always hold up. Firstly, “price changes are not independent of each other”, writes Mandelbrot. Although “it is not a well-behaved, predictable pattern”, there is instead a “fractal kind of statistical relationship, a ‘long memory’”, he says.

Secondly, the statistical nature of price behavior is not always stationary. Volatility is volatile, and “price-changes in a financial market can cluster into zones of high drama and slow evolution.” Thirdly, “price movements do not follow the well-mannered bell curve.” There are just “too many big changes.” From cotton prices to railroad stocks, “the tails [of price changes] do not become imperceptible but follow a power law.”

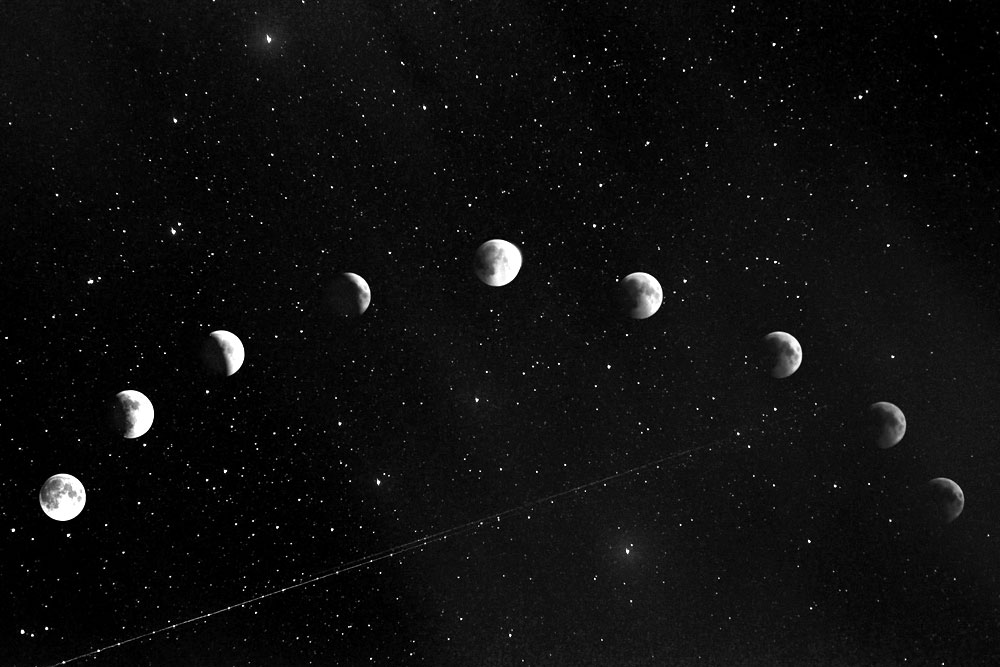

Put together, these findings tell us that markets are “more risky than the standard theories imagine.” Big jumps are not as rare or as surprising as is commonly assumed. “Trouble runs in streaks”, Mandelbrot reminds. “Market turbulence tends to cluster.” In this light, “patterns [can be] the fool’s gold of financial markets… The power of chance suffices to create spurious patterns and pseudo-cycles that… appear predictable and bankable.” The “financial market is especially prone to such statistical mirages.”

“Greater knowledge of a danger permits greater safety. For centuries, shipbuilders have put care into the design of their hulls and sails. They know that, in most cases, the sea is moderate. But they also know that typhoons arise and hurricanes happen. They design not just for the 95 percent of sailing days when the weather is clement, but also for the other 5 percent, when storms blow and their skill is tested. The financiers and investors of the world are, at the moment, like mariners who heed no weather warnings.”

Benoit Mandelbrot and Richard Hudson. (2004). The Misbehaviour of Markets.

In between astrologers

Why then do economists and business schools continue to teach their orthodox theories without caveats or alternatives? Mandelbrot likens the issue to the religious clerics that cling to heliocentrism despite all the evidence of astronomy. Ironically, the pervasiveness of modern finance is in part behavioral. “Economics is faddish”, Mandelbrot reminds. Their math “gives a comforting impression of precision and competence”, which helps to peddle more products. “It is false confidence, of course.” But when legions of students and professionals are trained every year in the same way, lock-in inevitably sets in.

To be fair, attempts have been made to reconcile the weaknesses of orthodox assumptions with the likes of arbitrage pricing theory (APT) and generalized autoregressive conditional heteroskedasticity (GARCH) models. But to Mandelbrot, “such ad hoc fixes are medieval.” They do not build upon the market dynamics and human behaviors we’ve seen to date.

“The classical theorists resemble Euclidean geometers in a non-Euclidean world who, discovering that in experience straight lines apparently parallel often meet, rebuke the lines for not keeping straight—as the only remedy for the unfortunate collisions which are occurring. Yet, in truth, there is no remedy except to throw over the axiom of parallels and to work out a non-Euclidean geometry. Something similar is required today in economics.”

John Maynard Keynes. (1936). The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money.

New frontiers in finance

So where do we go from here? After all, as Hans Rosling writes in Factfulness, “misconceptions disappear only if there is some equally simple but more relevant way of thinking to replace them.” And on that front, we do not yet have a clearcut alternative.

Mandelbrot himself is hopeful about the future applications of fractal geometry in finance, which draws upon the concepts of power laws, self-similarities, and fractal dimensions to explain the turbulent misbehaviors of markets. Multifractal Model of Asset Returns (MMAR) and Extreme Value Theory (EVT), he suggests, show promise.

In behavioral finance, Shleifer shows how a theory of investor sentiment and market limitations can explain market dynamics. George Soros posits something similar in his principle of reflexivity. He describes how complex interactions and feedback loops between participants can culminate in bubbles and super bubbles.

Finance may also find new ideas in the life and complexity sciences. Andrew Lo’s Adaptive Market Hypothesis, for example, uses the processes of learning, failure, and adaptation to explain the evolution of markets. Per Bak, likewise, explains how self organized criticality, as seen in earthquakes and avalanches, may apply to economic systems and financial markets.

While we do not have room to cover each of those theories here, their ideas are promising. Mandelbrot notes, however, that “it took more than sixty years after Bachelier’s thesis for economists… [to] formulate the Efficient Market Hypothesis, and another decade… to find valuable applications in the real world.” Clearly, we’ve got a lot of work ahead of us. But for the mavericks of finance and economics, this should excite you.

Sources and further reading

- Rosling, Hans., Rosling, Ola., & Rosling Rönnlund, Anna. (2018). Factfulness.

- Taleb, Nassim. (2017). Skin in the Game: Hidden Asymmetries in Daily Life.

- Mandelbrot, Benoit., & Hudson, Richard. (2004). The Misbehavior of Markets.

- Keynes, John M. (1936). The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money.

- Buffett, Warren. (1984). The Superinvestors of Graham-and-Doddsville.

Latest posts

- Arguing with Zombies — Paul Krugman on Bad Models and False Idols

- Raghuram Rajan on Financial Development and the Making of a Riskier World

- The Winner’s Curse — Richard Thaler on the Anomalies of Auctions

- The Market for Lemons — George Akerlof on Asymmetry, Uncertainty and Information

- Reflexivity and Resonance — Beunza & Stark on Quantitative Models and Systemic Risk

- Power Laws — Mark Newman on Solar Flares, Gambling Ruins and Forest Fires

- Heresies of Finance — Benoit Mandelbrot on Volatile Volatility and Valueless Value

- Financial Instability Hypothesis — Hyman Minsky on Ponzi Finance and Speculative Regimes

- Constructing a Market — MacKenzie and Millo on Performativity and Legitimacy in Economics

- The Wrong Track — Benoit Mandelbrot on the Future of Finance